2012 Assessment:

2012 Assessment: None -- it's not on the novels list.

Current Reading: Eye-read in a cheapish ~80 year old edition.

Dickens’

A Child’s History of England isn’t a novel, but just what the title claims: a history of England, pitched at the level of a bright child, often with the kind of jolly bluster you might aim at a somewhat dim child. My copy, an orphan from a complete hardcover set of Dickens – undated, but I’ll guess 1930ish – has a strikingly tepid introduction. “Forster remarks that he ‘cannot be said to have quite hit the mark with it,’” reports the anonymous editor, “yet it seems that to demand anything much better of its kind and for its purpose would be to demand more than is humanly possible.” Right on! Something hardly worth reading, that even Dickens’ buddy and biographer John Forster found mediocre! Way to sell the book, anonymous editor!

A review I noticed online said that the vocabulary was way too tough for any child, and that you better have your dictionary beside you when you read it. This is simply not true. The vocabulary would never challenge any middle school student who would choose to read the book. Dickens does not seem to have put much effort into simplifying sentence structure, however, and I reckon that this is what makes the text seem difficult to some readers.

I actually found it surprisingly entertaining reading. I kept it as bedside reading for a couple of weeks, and it fit that niche beautifully. It was pleasant enough to look forward to, and just dull enough to facilitate the drifting-off process. Dickens’ patent anti-Catholicism is unseemly, but mitigated by his honest disgust at the strain of anti-Catholicism in English history. We are full of contradictions, all of us.

I said at the beginning that

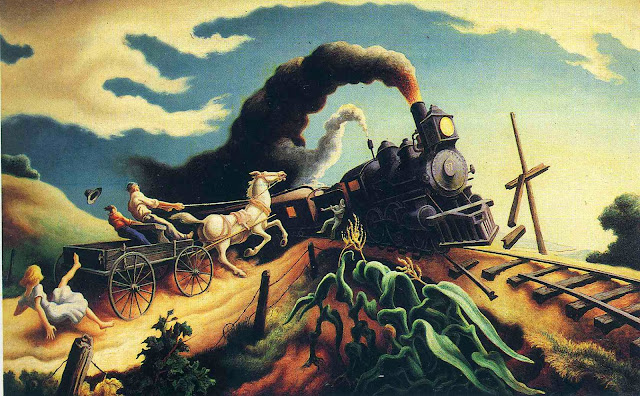

A Child’s History of England is a history of England, but that’s not quite right. It is a history of the people who held and contended for the English crown. That’s the way that history used to be conceived, of course, and the most interesting thing about reading Dickens’ take is seeing a prime example of how blinkered the traditional school of “Great Man History” really was. A chapter with a title like “England Under Henry the Third,” for instance, says absolutely nothing about what was happening in England during the reign of Henry III – only what happened to Henry III. England itself – its population, economy, laws, culture, towns, transportation network, crops, the whole green and pleasant land – does not really make an appearance in this book. Here is the English intellectual tradition:

That reign (of Elizabeth I) had been a glorious one, and is made forever memorable by the distinguished men who flourished in it. Apart from the great voyagers, statesmen, and scholars, whom it produced, the names of Bacon, Spenser, and Shakespeare, will always be remembered with pride and veneration by the civilized world, and will always impart (though with no great reason, perhaps) some portion of their lustre to the name of Elizabeth herself.

That’s it. Really, that is the sum total that Dickens dedicates to the arts and sciences. And along with an occasional mention that a king’s reign was troubled by the plague or the Great Fire of London, it’s as close as the book ever gets to the history of England as a country, as opposed to England as a crown. It seems like a bit of a train wreck if you’ve never been exposed to seriously old school historiography, but in the 1850s the monomaniacal focus probably didn’t raise an eyebrow. That’s just what history was.

Despite that Dickens only took history up to the Cromwell years, which were as remote in time to him as the American Civil War is to us today, we have it (although not on terrific authority) that his

Child’s History of England was widely used in British schools for 90 years, right up to the second world war. Today, it is hardly read at all, except by myself.

Plot: Various powerful people struggle for even more power, but even when they get it, it doesn't usually make them happy. The ones that you'd want to hang out with aren't necessarily the most effective, but on the other hand the real bastards are always big trouble.

Prognosis: More interesting as historical artifact than as history.

Current Dickens Score: Unchanged, as this was not on the novels list. I have still read

9/14.5 of the non-Christmassy Dickens novels.

Second Opinion: There are abundant editions available in every conceivable online format, because it is a public-domain work by a popular author. Since no one actually reads it, however, there's not much online conversation about it.