Guns, Germs, and Steel

Guns, Germs, and SteelA long time ago, in a Midwestern state far, far away, I regularly taught classes in “World Regional Geography” to small auditoriums full of

I’ve never really missed that job – until now. Now, I want to go back and design a course that isn't structured around the appallingly fragmented textbooks I knowingly inflicted on the students back in the day. Instead, I want to design a class around texts like Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel.

So What’s it All About?

Our history as a species is kind of complicated, and of course there are a lot of zigs and zags in the pattern. What Diamond is able to do is zoom way back to a level where the big, prevailing pattern of history becomes clear. And that pattern goes like this: over time, dense agricultural societies tend to win.

So far, so good. But why do some societies become dense and agriculture while others don’t? Why did the good people of the Fertile Crescent and the Chinese plains develop dense agriculture early on while the good people of the highland Americas developed it late and the good people of Australia and so many other places developed it not at all? The answer, it turns out, is pretty much that people developed dense agriculture… wherever they could.

See, where geographers and the like had gone wrong in thinking about this before is by focusing on climate. This had gone so very, very badly – to the tune of “people in temperate climates are quick-witted and vigorous, while people in tropical climates are stupid and lazy” – that there was a reaction against even thinking about the effect of environment on culture for several decades. After all, even when you strip away any implicit racism, thinking about climate's influence on culture leaves holes big enough to march a marauding army through, such as -- to pick one of a thousand possible examples -- why did dense urban civilization develop in the Mediterranean climate of the Mediterranean, but not the Mediterranean climates of California, coastal Chile, or South Africa?

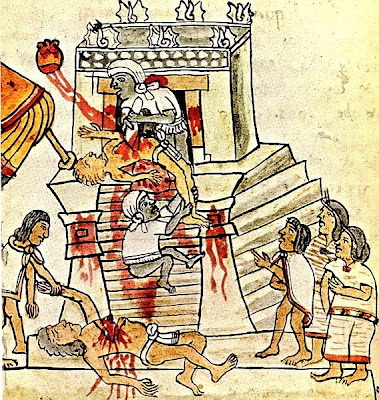

It turns out that the key factor isn’t climate, but the plants and animals that happen to live in your neighborhood. Clever ecologists have looked at native wild grains and other starchy, empire-buildin’ types of plants, compared their relative gross yield of calories and proteins among several other factors, and determined that the ones that ended up getting domesticated were, well, the best ones. In other words, wheat isn’t just one grain out of an infinity of plants out there that people might have domesticated. It was, instead, a virtual time-bomb of potential human utility that all but guaranteed an enormous competitive advantage to the first society that domesticated it on a sustained basis. (If you are wondering why corn didn’t have the same explosive impact in the Americas, the answer is only it didn’t have time to; the ancestor species of the behemoth corn we eat today was teeny tiny, and the grain just hadn’t been bred big enough for long enough to fuel the explosive level of socio-technological development that would have let the Aztecs sail over to Europe and kick some, say, Danish butt.)

There are, similarly, a lot of different kinds of animals in the world, and if you are like me you might assume that it is just a random few that happened to get domesticated. Diamond is able to make a pretty convincing argument – the jury isn’t entirely in on this one, but they are working on it – that no, the animals that got domesticated are the ones that could be domesticated. Bears, tigers, zebras, elephants, rhinos: sure, all might make superb eatin’, or great draft animals, or pass on terrifically deadly diseases for you – but it ain’t gonna happen. For various reasons dealing with hard-wired animal psychology, you simply can’t domesticate them. Happening to live near ancestral cows, sheep, goats and so on was thus a way of drawing a very high card in the game of societal competition. Ending up on a continent like Africa, where the abundant megafauna just happens to be resistant to domestication, or like Australia, where everything but a single kind of kangaroo was wiped out in the excitement of the first arrival of human beings several thousand years ago, is just plain bad luck.

“Now wait,” you might be thinking. “This is raw determinism! Just because a society lives around ancestral wheat and ancestral goats doesn’t mean they will choose to make the big switch from hunting and gathering to sedentary farming.” And indeed not. In fact, you could make a case that the smarter societies would avoid such a thing at all costs, because hunting and gathering in a productive environment was a highly chill sort of lifestyle compared with the brutal drudgery of farming.

Well, That’s History for You

There’s more work to be done on grand-scale history, to be sure. And Diamond even makes a fairly glaring misstep, with a chapter about the relative benefits of having your continent oriented along a longitudinal axis versus a latitudinal axis. What he’s getting at is how ecological barriers can inhibit the flow of ideas, technologies, and those handy epidemic diseases, but couching this as a matter of continental orientation, when you have a sample size of three, is a bit daft. But by and large, I suspect that future work on the large-scale history of humanity will be a progressive refinement of, rather than a serious alternative to, the narrative that Diamond outlines here.

Some people, to be sure, will be bothered or appalled by such an amoral picture of history. We have raised to be in horror of the impositions of colonialism and imperialism, and in the better and fairer world that humanity has more or less been trying to build for the last little while, this is right and just. We recoil from the collective memory how the English wrested New Zealand from the Maori, and we recoil, though perhaps with some confusion, from Diamond’s telling of how the Maori wrested the Chatham Islands from their inhabitants, who they enslaved or slaughtered. We recoil from the heinous story of Cortez and the Aztecs, as we should, and if we dig in a little we will also grieve for the many cultures trampled under the bare but powerful foot of the Aztecs.

Human history is, alas, a story of bigger fish eating little fish, and in order to tell the story efficiently Diamond makes his sympathy for the little fish clear at the outset but does not repeat it in every paragraph. This lets him get beyond the well-meant but morally suspect story of history we teach our children – the story of how the big fish were wicked and the little fish were virtuous. Wickedness trumps virtue, we tell them, and that’s more or less how things came to be as they are.

Human history is, alas, a story of bigger fish eating little fish, and in order to tell the story efficiently Diamond makes his sympathy for the little fish clear at the outset but does not repeat it in every paragraph. This lets him get beyond the well-meant but morally suspect story of history we teach our children – the story of how the big fish were wicked and the little fish were virtuous. Wickedness trumps virtue, we tell them, and that’s more or less how things came to be as they are.

.jpg)