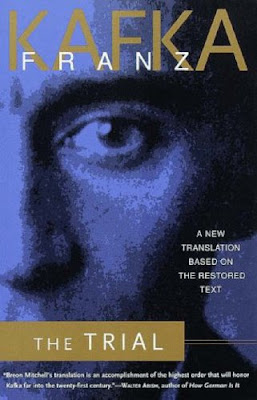

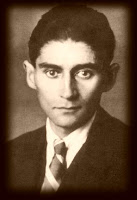

I've long thought of Kafka as probably the most important and influential writer that I'd never read -- except of course for that bit about the guy changing into the bug, and I’m not sure whether I’ve actually read that one so much as heard a lot about it over the years. It turns out that while I was reading The Trial, a number of people told me the same thing about themselves. We all imagine Kafka looming like, I don't know, like an enormous bug over twentieth century fiction. And that’s apparently accurate, too -- the dark comic irony and straight-faced, formal absurdities of many of the great postmodern authors trace much of their inspiration to the works of Kafka. We don't call the struggle of the alienated individual against the bizarre systems wrought by mysterious social forces "Kafkaesque" for nothing. (In fact, we call them "Kafkaesque" because we are big show-offs. But that's neither here nor there.)

I was kind of surprised, then, to learn that Kafka was virtually unknown during his own lifetime, and that it was only after the Second World War, a couple of decades after his death, that his works suddenly attained popularity and respect. His literary star must have risen with hand in hand existentialism, a philosophical movement perfectly attuned to his protagonists' alienated struggles against the absurd, but his reputation seems to have fared better than other existentialists, like Camus and Sartre, up into the present. I can't say much about that, never having read much Camus or Sartre.

Yeah, Yeah, But Did You LIKE It?

I sure expected too. Many of my favorite writers, Saramago or Murikami for instance, have been described as "Kafkaesque." Hell, "The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy" and "Monty Python's Flying Circus" are sometimes said to have Kafkaesque elements to them. I like dark absurdity! I'm all in favor of the surreal! I can't get enough of an ironically formal writing style!

And yet, no, I didn't like The Trial. I can recognize its obvious importance and influence, but I didn't enjoy it and can’t really recommend it on its own merits as an enjoyable read.

My objections are four. In reverse order of (self-perceived) sophistication, they are: 1) it's kind of boring, 2) it's kind of depressing, 3) its composition is disjointed, and 4) it cheats on its social critique.

I won't dwell on the first two. To say "this literary classic is kind of boring" is practically to say "I haz short attention span!" In my defense, the novel is all about a process (in German, the word for "trial" is Der Process) that goes on and on and on without any progress or resolution. Also, Kafka deliberately writes in a highly precise and formal style. Neither of these aspects of the novel are slam-dunk ingredients for an engrossing read. Similarly, to say "it's kind of depressing" is like saying "I can't handle looking grim reality in the face!" But I would say that Kafka painted a grimmer picture in The Trial than actual human existence normally justifies. More on that in a bit.

I won't dwell on the first two. To say "this literary classic is kind of boring" is practically to say "I haz short attention span!" In my defense, the novel is all about a process (in German, the word for "trial" is Der Process) that goes on and on and on without any progress or resolution. Also, Kafka deliberately writes in a highly precise and formal style. Neither of these aspects of the novel are slam-dunk ingredients for an engrossing read. Similarly, to say "it's kind of depressing" is like saying "I can't handle looking grim reality in the face!" But I would say that Kafka painted a grimmer picture in The Trial than actual human existence normally justifies. More on that in a bit.That the composition is disjointed isn't really Kafka's fault; he died while the book was still in a rough draft. Nobody's sure which order the chapters are supposed to be in, and there are picky little continuity errors here and there. The foreword to my edition didn't mention the possibility of missing chapters, but I have to assume that Kafka intended to write some more material between the penultimate and final chapters. As things stand, the ending jumps out of nowhere and does not feel like a natural extension of or conclusion to the rest of the book. But who knows, maybe that's the way he wanted it.

The point of Kafka seems to be a protest against the alienating and grinding persecution of individuals by arbitrary and blandly bullying systems, systems that have been put in place by the anonymous powers that be. Well, fair enough. It's a denunciation of inhumanity, and I'm good with that. The problem is, in The Trial the protagonist's persecutors are so inhumane as to be inhuman. They -- indeed, all of the characters -- act and speak in such a stylized fashion that they are scarcely recognizable as human beings. Kafka's flat, surficial descriptive style further alienates the reader (which is to say: me) from the humanity of his characters, giving me no inkling of what might motivate them to their strange behaviors.

The upshot of all this is that Kafka's world is a lot grimmer than the real world -- usually. In the real world, when you are being ground down by the bureaucracy or the corporation or whatever the arbitrary and blandly bullying system might be, you are being ground down by real live human beings. Occasionally you might note their sadistic glee in your distress, sometimes their indifference, but usually you are going to notice that people in general will at least make an attempt at kindness, as long as it doesn't cost them anything. It may not be much, but it's better than Kafka's world.

A final irony, however, is that Kafka's siblings were all murdered in the Nazi concentration camps. They ended up living in and being killed by the grimmest and most horrific blandly bullying system yet devised. Kafka himself died of natural causes long before Hitler's rise to power, and thus escaped having to inhabit the kind of horror he imagined in his novel.

Plot: "Someone must have slandered Josef K.," the famous first line goes, "for one morning, without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested." He is not jailed, but is increasingly consumed by a trial that in some unknown, amorphous fashion, seems to be proceeding somewhere. We are never given any indication of what poor Mr. K's crime might have been; we merely watch as he bounces among the book’s minor characters, each of whom has their own specific advice about how he can attempt to secure a favorable outcome, and each of whom frankly confesses that, although their advice is sound, it never really works. Details throughout are so surreal as to be hallucinatory; the court where Josef K.'s case is apparently being tried is in the attic of a low-income tenement, and can only be entered through various residents' personal apartments.

While his trial may or may not be progressing, Mr. K makes a half-hearted pass at the girl across the hall, runs the rat race at the bank where he works, has an affair with a woman who has a thing for defendants, and waffles about whether to fire a lawyer who might be really good or might be really bad. All of these situations are completely absurd and arbitrary, and there is never any way for Mr. K to find out the truth of the situation, or even to gather information that might lead to an informed decision. All he can do is choose, and act, and any choice and any action is likely just as good as any other. Nothing he does will help much. This, Kafka suggests, is the human condition. He must have been a lot of fun at parties.